Foreword

- Most of the things you need to think about are described in the OHBM MRI COBIDAS.

To understand to subtilities of designs, QA and stats, you need some basic understanding of how MRI works. You can check this lecture I made a long time ago, assuming the univese hasn't changed, the MRI physics should still hold.

Experimental Designs

Functional MRI designs are more complicated than behavioral experimental designs as, in same time as thinking about experimental effects, we have to think about fMRI acquisition parameters. I present here key notions on the different types of fMRI designs (blocks, event related, mixed) and clues to 'optimize' these designs.

There are 3 main types of design: blocked, event-related or mixed. This classification operates on the way stimuli are presented. The optimization of these designs refers mainly on how to increase their power. Here, I discuss optimization of stimulus related parameters.

Block designs

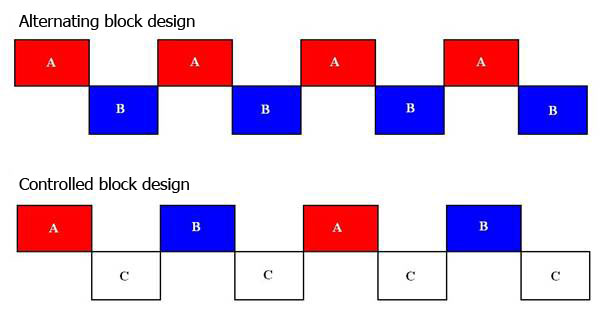

Block designs are well suited to localize functional areas and study steady state processes (e.g. attention). One can distinguish alternating blocks from controlled block designs. Alternating designs: conditions A and B are alternated in distinct blocks which is useful for determining which voxels show differential activity as a function of the variables (i.e. the difference between A & B). Controlled block designs: conditions A and B are separated by null-blocks, i.e. a control condition C. which allows the identification, in addition, of voxels activated by each condition separately and in both conditions.

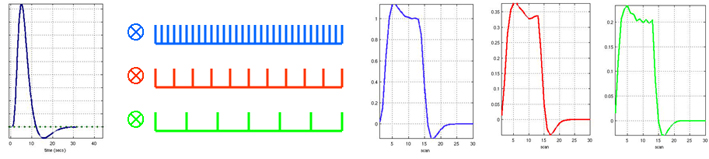

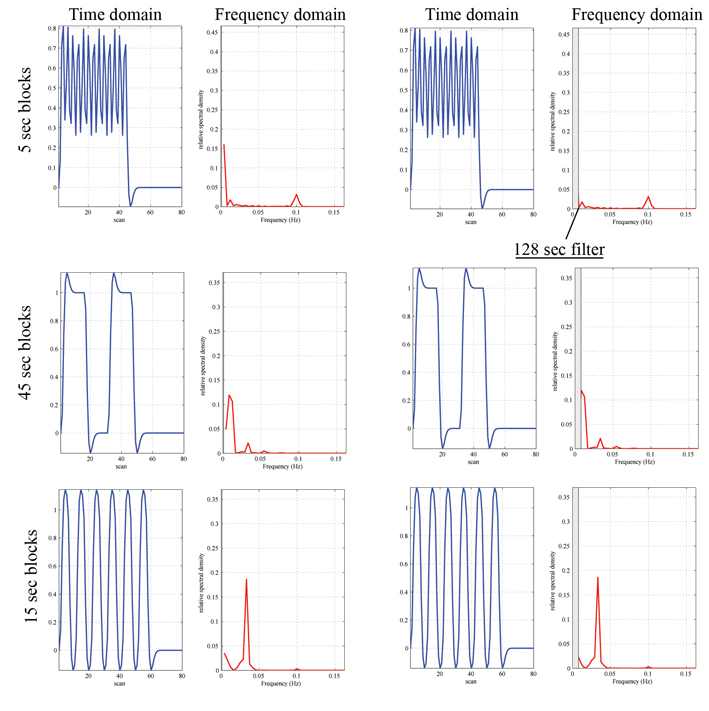

Block designs are powerful in terms of detection, i.e. to determine which voxels are activated. The advantage of short ISI is that the response is greater than for long ISI because responses to different stimuli summate thus increasing the response amplitude. On the other hand, because of summation of the hemodynamic responses iin time, block designs have a poor estimation power, i.e. a weak ability to determine the time course of the response.

Optimization: Signal strength varies with the length of blocks. With short blocks (less than 10s), the signal does not return to baseline during null-blocks decreasing the strength of the signal. With long block lengths, a large response is evoked during the task blocks and the response returns to baseline during null-blocks. However, the detection power increases with high frequency alternation because i) it depends on the number of events/blocks and ii) the noise in the BOLD time course which occurs mainly at low frequencies. Blocks with durations longer than the hemodynamic response reach a compromise between signal strength and noise (optimal 16s)

Event related deasigns

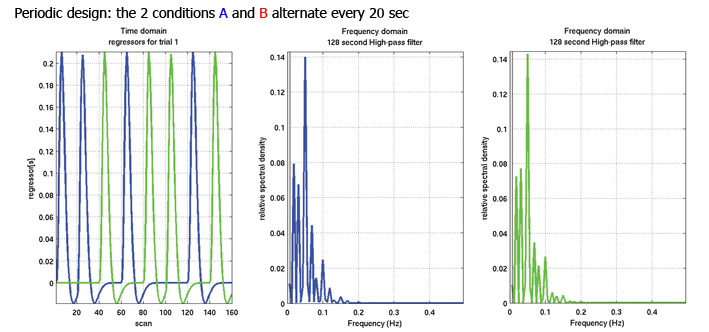

Each event is separated in time by an inter-stimulus interval ranging from few sec to tens of seconds. Event related designs are based on the assumption that neural activity will occur for short and discrete intervals. Such designs attempt to measure transient changes in brain activity. Unlike blocked designs, stimuli are presented in a random order rather than an alternating pattern offering a higher flexibility in experimental terms. Estimation power of event-related design is often good as they allow to inquire the hemodynamic shape for each condition and compare parameters such as the amplitude or the timing between conditions. By contrast, the detection power is relatively weak in comparison with blocked design. This is explained by the simple fact that experimental power depends on the number of events that are averaged.

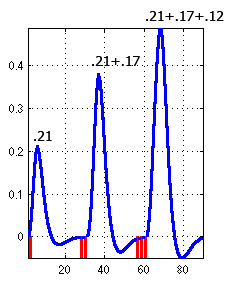

In rapid event related designs, stimuli are closely spaced in time, i.e. there is an overlap of the hemodynamic responses. Raw signal is often uninterpretable but trials can be in a total random sequence such as it is highly resistant to habituation, set, and expectation. By introducing ‘null events’ one creates differential ISI, i.e. differential overlaps between hemodynamic responses which allows a full characterization of this response. Different techniques exist to 'randomize' the stimuli alternation.

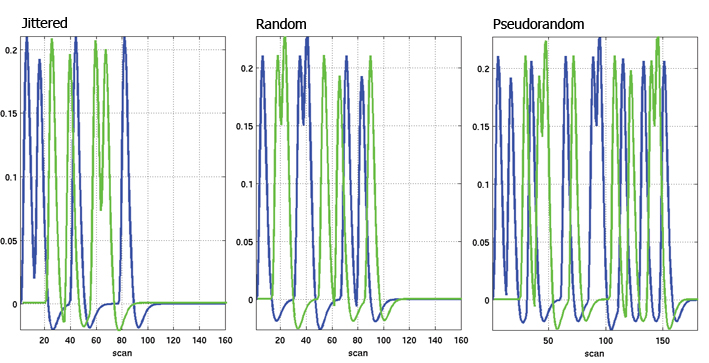

Randomized designs rely on the likelihood of a stimulus being presented at each time point.

Stationary stochastic designs rely on the likelihood of a given ISI following each stimulus ('jittered' designs).

Dynamic stochastic designs rely on the systematic probability variation of stimuli over time ('semi-random' designs)

Adaptation designs

fMRI adaptation designs (afMRI) use the refractory period to enquire functional differences within a given region. The predicted hemodynamic response relies often on a linear prediction. This means that for an impulse (a short-duration stimulus), the hemodynamic system responds in the same manner. The parameters of the hemodynamic response are then directly interpreted as reflecting both the intensity and the duration of the neural response given the scaling (the magnitude of the system output is proportional to the system input) and superposition (the total response to a set of inputs is the sum of individual inputs) properties of linear systems. The hemodynamic response is linear for ISI > 6s and nearly linear down to ISI ~ 3/4s. If the ISI is short, the response to a subsequent stimuli is weaker than for a longer ISI (Boynton and al., 1996, J Neurosci 16, 4207-4221; Dale & Buckner, 1997, Hum Br Map 5, 329-340). This phenomenon is known as the hemodynamic refractory period. Such a refractory period has been used to investigate neural adaptation effects.

Issue: an area showing an adaptation effect can receive inputs from an area which does code stimulus properties (real adaptation effect) but does not by itself has neural specificity. Although most adaptation designs rely on some sort fast-event related designs, Aguirre (Aguirre, NeuroImage, 35, 2007) demonstrated that on can use a continuous stimulation where stimuli change their properties from one trial to the other, i.e. a design where we look at the effect of the previous stimulus on the current response (carry-over design).

Mixed designs

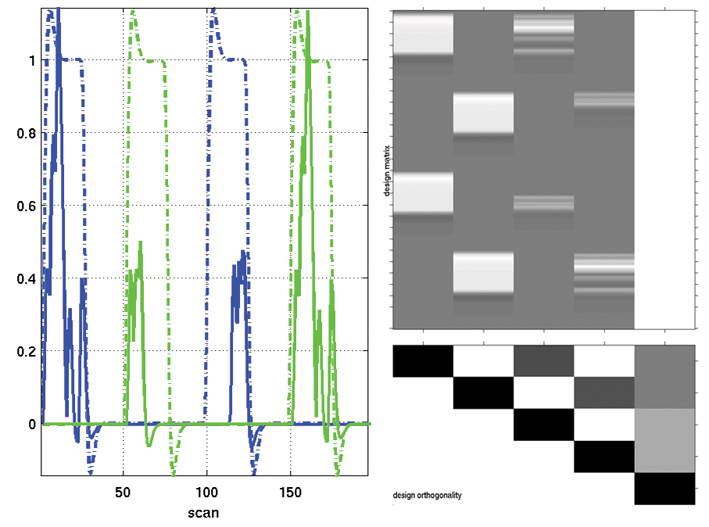

Stimuli are displayed in discrete blocks which allows investigating sustained processes and brain responses (state-related processes). This however is different from semirandom designs where, whatever the stimulation rate, we assume that the process is always the same (looking for transient activity for each stimulus). Within each block multiple types of events occurs and because there is different types of stimuli, transient responses are also likely to occurs. Therefore, mixed designs can investigate interaction between processes working at different time-scales.

Quality Assurance and Noise

We are getting into the nitty-gritty of fMRI here. There are many aspect of the signal that needs to be quantified, from the raw data, but also for the various stage of the data procesing workflow. I wrote about this in two blogs about Cleaning time series and measure fmri noise. There are of course all the other usual motion artefacts and associated metrics. Check out the SPMUP project that tries to measure and incorporate all of that in your analyses.

fMRI Statistics

Single subject thresholding - clinical application

At the subject level, the distributon of statistical values is not always central - i.e. centered on 0. The implication of this is that thresholding can thus grossly under- or over- represent the effect. A proposed solution is to model the distribution as a mixture of a non central Gaussian (the null) and positive/negative Gamma distibutions for the tails (signitifcant activations/deactivations). Chosing the crossing point(s) of crossing distributions end-up separating signal to noise, obtimizing the false positives/false negative ratio. See Gorgolewski et al. 2012 and get the code for SPM here.

Boosting your Beta estimates

A time series regressor models a given condition across trials, and it's fit thus represent the mean. If the hrf is mis-specified starting for instance earlier than the standard model, adding the derivative gives a better model. Only the combination of parameters gives a good model, the amplitude of the hrf is still wrong and need to be 'corrected'. You can read more about this in the tutorial paper, and get code for SPM here

Computing the percentage signal change

After convoluting the stimulus/condition/task regressors by the hrf, the design matrix doesn't scale to 1. This means that the model parameters need to be rescaled do have a meaningful unit. Such unit can be 1, but also the maximum of a reference trial or of the current design - this is as arbitrary as choosing to express a value in pounds, euros or dollars. You can read more about this in the tutorial paper, and get code for SPM here

Lectures

You can access several of my lectures slides here:

-fMRI statistics and inference

SPM Edinburgh course (curated archive 2010/2019)

Thank you to all my friends and colleagues who gave lectures over the years: Dr Devasuda Anblagan, Dr John Ashburner, Dr Roselyne Chauvin, Dr Ian Charest, Dr Justin Chumbley, Dr Jean Daunizeau, Dr Christian Gaser, Dr Nikolaus Kriegeskorte, Dr Daniele Marinazzo, Dr Martin McFarquhar, Dr Alexa Morcom, Dr Thomas Nichols, Dr Jean-Baptiste Poline, Dr Christophe Phillips, Dr Mohamed Seghier, Dr Jason Taylor & Dr Thomas Wolpers. Thank you to the hundreds of colleagues and students how attended the course.

- MRI physics: what are we measuring?

Preprocessing MRI-fMRI

- Within subject preprocessing: (fMRI) slice timing correction

- Within subject preprocessing: realign and coregister

- Between subject preprocessing: normalize and smooth

-Morphometry for volumes and surfaces

Experimental and fMRI Designs

Univariate Statistical Modelling

Multivariate Statistical Modelling

Representation Similarity Analysis

Statistical Inference and Visualization

Designs and Inference for fMRI

Inference in univariate and multivariate models

Multiple Comparisons correction

Multiple Comparisons correction, levels of inference, circularity

Inference and Result Visualization

Bayesian modeling and inference

Bayes probability, modeling and use in SPM

Bayesian inference: model comparison and model selection

Multivariate Bayes for decoding

Connectivity

Functional connectivity in fMRI

Dynamic Causal Modelling overview

Multimodal Imaging